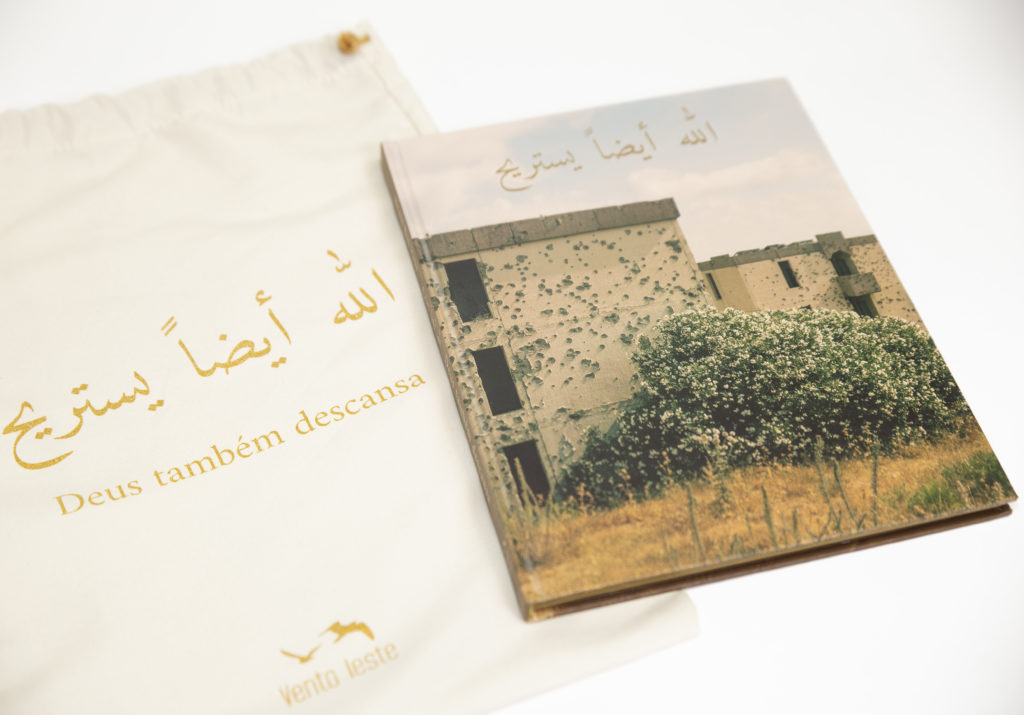

São Paulo – The photographer Bruno Bou Haya took his first trip to Lebanon alongside his mother in July 2019, to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the coming to Brazil of his Lebanese grandparents. He recently released photos taken across the country during the trip, including ones from his grandparents’ village of Beit Menzer. The photobook “Deus também descansa” (Portuguese for ‘God Also Rests) is out from publishing house Vento Leste.

“My mother had been [to Lebanon] before with my grandmother. I’d never been there, and I didn’t meet my grandparents either. I took the trip to connect with the culture that was in my home before the passing of my grandparents. With an identity that’s an inevitable part of me, like my complexion, my strong Arab features: the beard, the thick eyebrows… I have always been in this place of a Lebanese descendant because of that,” Haya told ANBA. He argues that his father, who’s of Portuguese and Italian descent, also has Arab features. “Looking back at my father’s genealogy, I would surely find that it’s in Moorish territory, no doubt about it.”

Haya said he’d always wanted to see Lebanon more than he did Europe or the United States. “It was just a matter of time, because it would be like going home, and the seventieth anniversary of my grandparents’ migrating was a great occasion for us to take this trip together.” A friend of Haya’s mother who’s also a descendant tagged along.

His grandparents’ village is 110 km north of Beirut. “It’s a place on the hills where it snows, near a cedar forest. I went to the village, and much of the book features photos of the house my grandfather built. That’s where I stayed. There are photographs there of my Lebanese cousins and of my great-aunt’s home.”

The photographer’s Lebanese family are Maronite Christians. Haya himself is agnostic, but God is in his book’s title. He said the idea came during the trip: “I’d been seeking a name, a magnet that would pull the images together, and ‘God also rests’ felt interesting because when I looked at all that landscape, I – an agnostic who’s once been an atheist – identified Lebanon as a truly holy land. And that’s not just a figure of speech. And when you come upon such a beautiful landscape, you also find social ills. I see lots of similarities with Brazil, both the beauty and the twisted societal structure. The title is an homage to that holy land, and it also looks at these problems squarely, but respectfully. It’s this conflation of sacred and profane, with the human flaws that came about once God took his rest. It’s the author’s hypothesis for the rights and the wrongs of this land, even though it’s holy. It’s a really similar country to Brazil, but they have the transversality of religion.”

Haya made a point of seeing as much of the Arab country as he could. “It was interesting to get a more holistic picture of Lebanon, and since it’s a small country, it wasn’t hard to see it from North to South.”

[metaslider id=291220]

The photographer said the thing he liked the most about the trip isn’t on the material realm. “I had lots of misgivings as a descendant who’d heard stories about Lebanon since forever. I though the country’s beauty and qualities might be romanticized by the immigrants. When I went, I realized that what they used to tell me is part of the materiality, of the sentiment of the land. And I don’t mean just the residents, because the Lebanese love their country, they love their land, and that’s easy to tell even if you’re just visiting. You can sense the love in things, and you understand why, so that was really important to me. It was crucial.”

Even as a descendant, before going to Lebanon, Haya realized there was ignorance surrounding the place. “We identify Lebanon as a Middle East country, an almost desert-like setting, but it sits in the Mediterranean, there’s something of Greece and Italy about it. And so the most important thing was to identify that beauty, and the fact that what I’d always heard about is real, it’s not just romanticizing, and to identify those Mediterranean features.”

Haya worked on the graphic design for the book for a year after the trip, and the work was completed weeks before the Port of Beirut diaster in August 2020. “At that moment I felt really powerless, because once you get to know the territory, the relevance of the port, the history of Lebanon, you become eager to help. I was sad and shaken, and I thought that might be the right moment to discuss this connection, these ties Brazil has with Lebanon. And the book features research into this connection.”

[metaslider id=291213]

The photographer said this connection predates even the arrival of the first immigrants. “Both see nature as part of their country. Brazil is named after the ‘pau-brasil’ tree, and the cedar is the symbol on the Lebanese flag. There are ties that go back to the founding of the nations. No matter how far apart, they are really close.”

The 96-page book features 50 photo, with text in Portuguese, English and Arabic. In addition to photographs by Haya, it includes ones from his grandparents’ collection. It also includes a copy of a 1964 edition of newspaper “O Cedro,” by Lebanese immigrants in Brazil, with an obituary on the passing of his great-uncle, and a postcard from the author with notes about Lebanon. “The postcard is a short letter, a brief history of Lebanon, including the occupations and empires. The book concludes with that, and I rely on the postcard, which is a form of communication from a distance, to reference the diaspora.”

The book is about connections, Haya says. “Brazil and Lebanon, the private and the public, the question of my individual family and society. I focus on my family to tell the tale of Lebanese migration, of this society that has been through so much, through the same things as my family.”

Quick facts

Deus também descansa

Bruno Bou Haya

Vento Leste publishing house

ISBN: 978-85-990732-4-3

96 pages

Contact info

@brunobou

+55 (21) 99956-6544

brunobouhayar@gmail.com

Translated by Gabriel Pomerancblum