São Paulo – United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Oman are just a few of the countries that have announced billion-dollar investments in the production of green hydrogen. Many nations have started focusing on the technology that promises to help solve the energy challenges of the 21st century as it doesn’t emit greenhouse gases. Brazil is one of them. And it’s not alone: There is a partnership signed between the Pecém Complex in Ceará and the Sohar Port in Oman for exchanging knowledge on the technology.

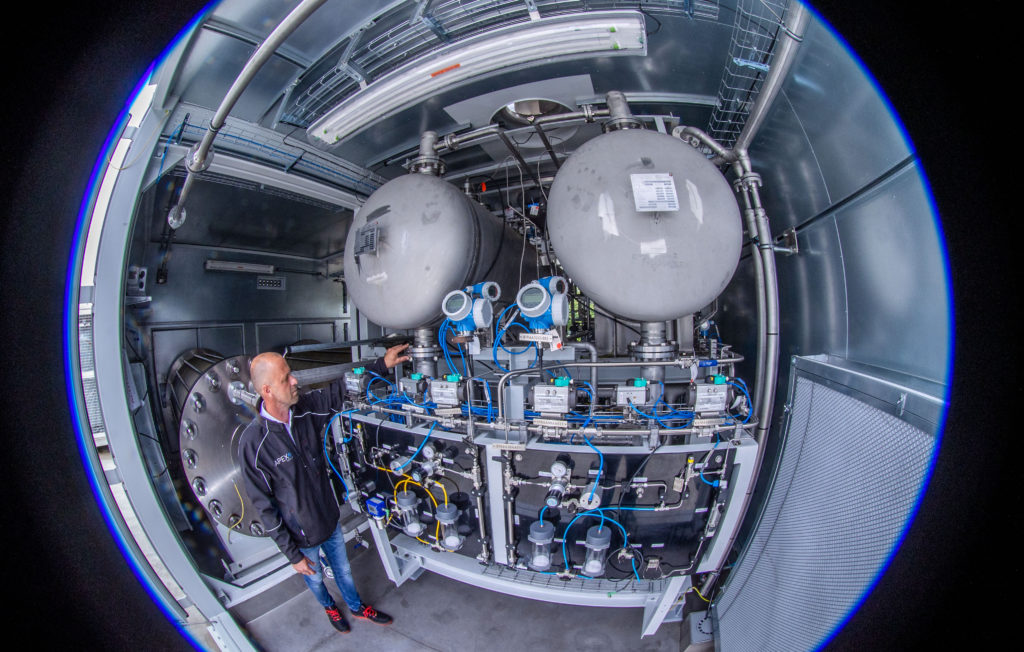

The hydrogen as an energy source can be extracted in a lot of different ways like from the production of ammonia, carbon sequestration, and the separation of hydrogen molecules (H2) from the oxygen molecule that form water. Pictured at the top of this article, a green hydrogen plant in Europe.

The hydrogen is considered green asit does not use any fossil fuel in its production and emits no carbon gas. Usually, a clean source such as solar or wind power sends the energy produced to the water reservoirs equipped with a device called electrolyser. This system separates the water into oxygen and hydrogen molecules. The hydrogen is obtained through this process to be used as fuel with an energy efficiency higher than gasoline, natural gas, coal, and others.

According to Ennio Peres da Silva, a researcher of the Interdisciplinary Center of Energy Planning and the head of the Hydrogen Laboratory at the State University of Campinas (Unicamp), the interest for green hydrogen has grown, and the fuel can even become a commodity – a good whose prices are determined by the market with no regard to who produced them – within a few years.

Aside from the Arab countries and Brazil, Germany, Australia, Uruguay, China and the United States are some of the countries with projects related to green oxygen at some stage of development and production of the fuel. “Each country has an interest and a chance to work with this technology. It’s an emerging market, and here in Brazil we’ve also made our project,” Silva says.

The professor says that, although the topic has picked up more and more steam due the growing demand for clean energy, it isn’t new. The technology for separating molecules of hydrogen from other molecules started back in the 70’s. Their precursors included Saudi Arabia and Brazil, which created the Hydrogen Laboratory at Unicamp due to the oil price crisis in the 70’s. Ups and down in oil prices, however, led to stops and starts in the development of the technologies in the 80’s, 90’s, 2000’s, 2010’s, and now.

“If the idea is not put on hold back again, the moment we live now is the third wave of hydrogen, and Arabs and Brazilians, including in the Northeast region, can benefit from it. The developments and outcomes obtained in the Arab world can be used here and vice versa,” Silva says. “But in both cases, the countries rely on international suppliers,” he finishes. The dependence arises from the fact that the technology exist but is still being refined. Electrolyzers are expensive devices produced by international suppliers. Another challenge is storing and exporting the hydrogen produced.

Nevertheless, projects have been developed everywhere, particularly in the Arab world: Egypt plans on investing USD 4 billion to obtain green hydrogen. Saudi Arabia will invest USD 5 billion in a wind-powered hydrogen plan. Abu Dhabi will spend USD 1 billion in a unit able to produce ammonia from green oxygen, while Oman is set to have the world’s largest green hydrogen plant using solar and wind power.

In Brazil, the Pecém Complex in Ceará is investing to build a green hydrogen production and distribution hub. Some memorandums of understanding have been signed with investments that could reach up to USD 10.5 billion. According to Pecém Complex commercial director Duna Uribe, part of the hub is estimated to be operating by 2025.

“The idea of having a production and distribution chain in the Pecém Complex is based on the goal that this H2V (green hydrogen) hub features producers and distributors of this kind of energy established in our Complex and even H2V storers, carriers and consumers, targeting particularly the countries that aim at cutting their energy generation/consumption greenhouse gas emissions to zero,” Uribe says, mentioning Germany and South Korea as examples. She also indicates that there’re opportunities for local companies, “which would be hydrogen-powered plants: steel, fertilizer, concrete, mining and petrochemical companies that are based or could be based in the Pecém Complex,” she said.

Regarding the partnership with the Sohar Port, Uribe said, “We’ve recently penned a partnership with the Sohar port in Oman, which is also a trade partner of the Port of Rotterdam like the Pecém Complex itself, and this commercial and technical cooperation agreement encompasses the interchange of knowledge and the development of technologies for Green Hydrogen (H2V) and other renewable energies,” she said.

Brazilian competitiveness

Brazil has the potential to “competitively” produce green hydrogen in large scale, says Brazil’s National Confederation of Industry (CNI) Environment and Sustainability executive manager Davi Bomtempo.

“According to figures from the latest Brazil Energy Balance made available, 83.0% of Brazil’s energy supply comes frow renewable sources. Therefore, the Brazilian industry has the potential to competitively produce green oxygen both for domestic consumption and exports,” Bomtempo says. He explains that the hydrogen has two main uses: final consumption and industrial raw material.

“As an industrial raw material, it serves to produce a variety of products. Most significant among these is ammonia, an extremely important raw material for Brazilian agribusiness,” Bomtempo illustrates. “As an energy source, the uses are still limited but very promising, particularly in regard to the development of new products related to the energy transport and supply sector,” he finishes.

Silva says there’re tests for using hydrogen as a fuel in trucks, trains, ships and buses. Japan’s automobile industry sells a hydrogen-powered car model in the U.S.

According to Bomtempo, Brazil has a huge hydrogen exploration potential, and the costs are expected to fall sharply from 2030 on. Therefore, there’s “homework to get done” such as a regulatory environment that could favor investment: “CNI believes that part of this framework will be covered by the National Hydrogen Plan that’s being developed under [Brazil’s] Ministry of Mines and Energy, but further rapprochement between public and private players is needed so that the regulatory framework actually contributes to Brazil’s technologic and industrial development,” Bomtempo finishes.

*Special report from Marcos Carrieri for ANBA

Translated by Guilherme Miranda