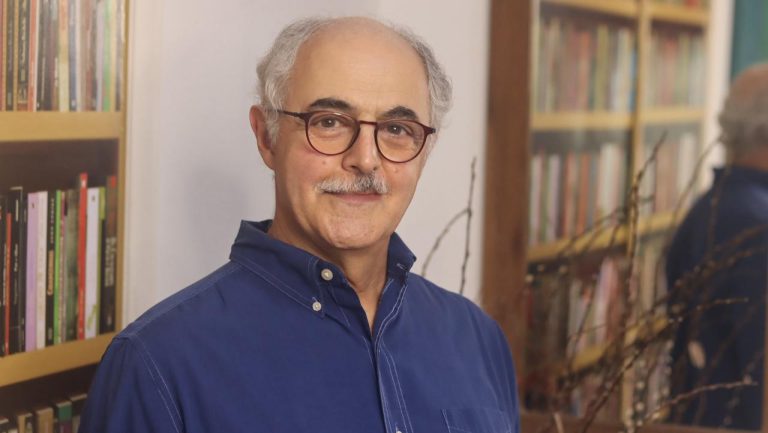

São Paulo – It wouldn’t be weird if São Paulo-born José Roberto Sadek, a grandson of Lebanese grandparents, had chosen to go down the wordsmithing path when choosing a career, as if the Arab tradition to tell stories had found in him a vessel to manifest – he went to study journalism in the University of São Paulo (USP). His PhD from the same institution was about how stories are told in the cinema and how it has served as reference to create Brazilian telenovelas.

His most recent book Séries e seriados: Para espectadores ligados e desligados também [TV series for all types of viewers], published by Giostri publishing house, gives information for viewers to better understand and enjoy TV series. The book also explains how the stories are organized, what characteristics retain the interest of viewers for so long, and what to look for in the first episodes.

When talking to ANBA, Sadek says he had never connected the Arab tradition of telling stories to his own career path and explains how this came to be. “As invitations came, I either accepted them or I didn’t. I went to USP’s School of Communication and Arts to study journalism, but people said I should get into cinema, because I photographed well, so I went.”

As invitations came, I either accepted them or I didn’t.

José Roberto Sadek

And so Sadek went, and as time went by, he says, he became a photographer, then he got tired from photography and became a screenwriter, and later on he was invited to direct a TV channel. “I go because I’m called to.” So, from call to call, he became a creation and production director at TV Escola, carried out special projects for São Paulo’s TV Cultura, was series director-general at TVE Rio de Janeiro, held office of secretary for culture of São Paulo state, and coordinated the Governor of the State of São Paulo Award for Culture.

Sadek in cinema and TV

When he graduated from cinema school, making movies was complicated and expensive, so he and a group of friends established a small production company that participated in public notices, tenders and bids. “We were ten lunatics – but we managed to win a bunch of prize money, and that’s how we managed to fund our next short film. It was hard work.”

We were ten lunatics – but we managed to win a bunch of prize money, and that’s how we managed to fund our next short film.

José Roberto Sadek

Sadek also worked at the Roberto Marinho Foundation and TV Globo, where he made films as a cinematography director and later as a screenwriter, and he says he made many episodes of Globo Repórter, a weekly newscast that has aired for 51 years. “Back then, we did TV on film. When I went to TV, within a week I shot more films than in some two years of independent cinema.” Now, among creative projects here and there, the cinema classes at the Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP) are the leading activity on his Linkedin profile.

Sadek was a Fullbright student in New York and graduated in architecture from the Mackenzie Presbyterian University, although he never practiced the profession. “I had studied in a religious school where there were only three admissable professions – doctor, lawyer and engineer.” He chose architecture. He believes he could have been a good doctor and had even considered the possibility but was discouraged by the memories he had from his father, a doctor who died from a heart attack and left him and his two younger sisters orphans when he was 15. “He told me the life of a doctor was harsh and to neve chose that profession.”

A son and a grandson

The death of his father would have been even more traumatic if it his mother hadn’t step up to ensure the rights of their children. “Those were hard times, family relations were complicated, but my father’s inheritance – which wasn’t much, though – supported us. We survived.” Without a father figure, he grew surrounded by women – mother, sisters, female cousins, aunts – which he deems a privilege. He is the happy father of two young women and is on his second marriage, and his wife has daughters, too. One of them has recently gave birth to a little girl. “You know, in parties I usually avoid the male cliques, whose talk is always about money, car and football. Women are much more interesting.”

my father’s inheritance – which wasn’t much, though – supported us. We survived.

José Roberto Sadek

From the Lebanese grandparents, he has just a distant recollection of his paternal grandfather teaching him to play backgammon. “I’d like to to relearn it, as I have a beautiful board of mother-of-pearl.” His mother’s mother lived in Espírito Santo, and in her house the 14 grandchildren from different states came together on summer vacations. “Grandma Alice was very fat, huge, and she used to spend the whole morning rolling kibbehs to feed that crowd that came back from the beach starving.” These cousins don’t meet that often anymore, but they remain in touch with each through a group text thread of which grandchildren, cousins and nephews and nieces want to be part, too.

Fifty years ago, during an unusual period, he went after self-knowledge and discovered and started practicing Tai Chi Chuan. He’s the student of the same master who first brought him into the Chinese martial art, and he now gives classes at his teacher’s gym. “That’s how it works, the older teach the younger.”

Read more:

A grandchild of Lebanese in the garden of Brazil’s Pedro II

Arab roots in Brazilian politics

Report by Paula Medeiros, especially for ANBA

Translated by Guilherme Miranda