São Paulo – Raimunda was only four years old when she left the port of Beirut behind. She doesn’t have many memories. As a small child, her recollections are a patchwork of others’ stories and old photographs. Upon arriving at the port of Santos, she met her father, who had left Lebanon years earlier to try his luck in Brazil. “We left the Lebanese winter and arrived in February, with intense heat and endless rain,” recalls Raimunda Abou Gebran, a retired professor from São Paulo State University (Unesp) and the University of Western São Paulo (Unoeste).

Alongside her older brother Michel Assali, her companion on the long 1956 journey (when they traveled with their mother and paternal grandmother), she wrote the book Entre verões e invernos: Estações de uma família libanesa [Between summers and winters: Seasons of a Lebanese family] (Scortecci Editora), launched at a large family celebration in November in São Paulo.

In the work, the siblings share memories of that journey: leaving the village of Ain-Hurche in the Bekaa Valley, crossing the Atlantic, reuniting with their father at the port, and traveling from Santos to Assis in the state of São Paulo, where their father had settled among a large community from their Lebanese village already living there.

“All immigrants talk about the lush coastal mountains upon arriving in Santos, but we saw nothing because it rained so much,” recalls Michel, who also became a professor and worked in education his whole life, retiring during the pandemic.

Their paternal grandmother, Marian, born in 1901, came with them and died in Brazil without ever speaking Portuguese. At 67, she traveled alone to Canada to visit some siblings, without knowing a word of English. According to Raimunda, she was the family’s great storyteller, and it was from her that the siblings inherited many of their family memories. Much of the book focuses on their father, Youssef, and his mother, Marian, whose husband had left for Argentina years earlier, leaving her alone with their son. The family never reunited.

The so-called Lebanese diaspora is full of stories like that of the Abou Assali family (Gebran is Raimunda’s husband’s surname, also of Lebanese origin), of people leaving a rural Lebanon, where hard labor on the land could not fill the family’s table, and setting off in pursuit of the dream of “making it” in the Americas. The siblings’ own family spread across Canada, Brazil, and Argentina—some stayed in Lebanon—so that many never saw each other again.

New land

When Youssef arrived in Assis, a city now with over one hundred thousand inhabitants, 434 km from São Paulo city, he followed the handbook of Arabs coming to Brazil: he hawked goods for three years before opening his own store. By the time his family arrived, his financial situation had already improved. One week after arriving in Assis, the siblings went to school… speaking Arabic. “Imagine the bullying!” says Raimunda, laughing. “That’s something you never forget!” adds her older brother.

Fortunately, the learning was quick, and Raimunda never lost her Arabic, a language she still speaks fluently today. Michel understands it but no longer speaks with the fluency he had as a child. She visited Lebanon four times, including trips to the village where she was born and reunions with some relatives. Michel has been twice, once with his entire family.

Once settled in Assis, Roberto was born, the Brazilian son of Youssef and Faride, and the younger brother of Raimunda and Michel, who didn’t share their migratory experience. “Maybe that’s why the book was surprising for him too—he was moved,” says Raimunda. Her eldest granddaughter, at 18, was also struck by the hardships their ancestors faced.

“The main goal of the book is precisely for the new generations to know everything that had to be done, how much our parents and grandparents fought and had to leave behind, so that they could have the comfortable life they enjoy today,” says Michel, who regrets that his parents never got to see the beautiful family that came after. “It’s a shame they couldn’t see that we prospered—and that the grandchildren even more so.”

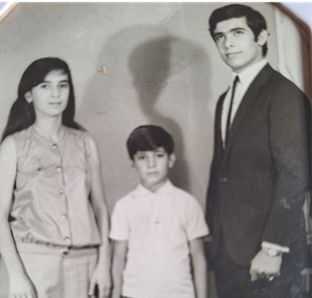

The book includes a series of documents that Raimunda kept in Assis (she has always lived there, while her brother moved to São Paulo, where he still lives), others found at the Immigration Museum in São Paulo, including one listing their names. It’s also filled with family photos, including one of the two brothers posing beside their father at the port, one of Michel’s favorites.

The story ends in 1968, when the family moved to the neighboring city of Presidente Prudente, beginning a new chapter, with the older siblings going to college and starting to forge their own paths. “That would be a whole other book,” says Raimunda. After all, the story continues to be lived and told by the new generations.

The book’s launch made such an impact in Assis that it ended up reaching other parts of Brazil. She says she even found out it was featured in a newspaper for the Brazilian community in Lebanon. What was meant to be a small, family-focused edition ended up sparking interest beyond the Abou Assali family—and beyond the Lebanese community.

Learn more about the book.

Read more:

Collection unveils new facts on Arab immigration to Brazil

Report by Débora Rubin, in collaboration with ANBA

Translated by Guilherme Miranda