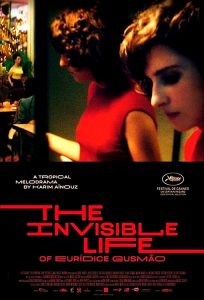

São Paulo – An Algerian engineer meets a Brazilian biochemist in Washington, D.C., United States, in the 1960s, and they get married. From this marriage came Karim Aïnouz, the film director who became the first Brazilian to win the Un Certain Regard top prize of the Cannes Film Festival. The victory came with the movie “The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão,” to be released in Brazil in November.

Known for “Madame Satã” and “Suely in the Sky,” the director gave a phone interview to ANBA from Berlin, Germany, where he has lived for ten years, to talk about his Arab background, his parents’ love story, the similarities between Ceará and Arab world, his film career, his first visit to his father’s land, and his new project, a documentary called “Algerian by Accident,” a result of his travel to Algeria, set to be released in 2020.

ANBA – Karim, which of your parents is Algerian?

Karim Aïnouz – My mother is from Ceará [Brazil] and my father from Algeria. He currently lives in Paris. I was raised by my mother in Fortaleza and moved to Paris to live with my father when I was 18. Most of my relationship with Algeria is through France, thanks to my father. But strangely enough, this year, before I finished “The Invisible Life,” I spent two months in Algeria for the first time in my life. I had never been there, and have just finished making a movie there, so now I’m editing what I filmed in Algeria, “Algerian by Accident,” which is a project that is kind of a seed of another project I intend to make in the next years, telling my parents’ love story.

How did your parents meet?

They met in the United States in the 1960s. My father was on the run. He had received death threats because he was fighting for Algeria’s independence – my grandfather was also part of the movement – and he had to run away from Algeria. At the time, the United States was flirting with Algeria because it was clear that it would become independent, so there was a trade and political flirt.

My father was a hydraulic engineer. He worked in the construction of Algeria’s road network in the 1960s and 1970s, and after he went to France, he kept working in construction in Algeria. He lives partly in Paris and partly in Algiers.

My mother worked with molecular biology, and she was a researcher and professor at the University of Fortaleza and for a long time worked doing research in partnership with the Pasteur Institute in Paris and a Scottish institution.

They met in Washington DC, during an English proficiency course. He went to live in Colorado and my mother in Wisconsin, and after a while she moved to Colorado to marry my father, and I was “made in Colorado” [laughter], but I was born in Ceará. My mother wanted me to be born there. I have Brazilian, French and Algerian citizenship.

They lived in the United States for five years, after my mother went back to Brazil and they split up, I stayed with her while my father went back to Algeria and eventually went to live in France in the late 1970s.

Therefore, “Algerian by Accident” is kind of a rehearsal for this fiction that is going to tell their story. They are people from two completely different cultures that found each other in a very important moment in history that is the independence of the African colonies. It was a very beautiful encounter between people from two different places in the Third World that were in a process of emancipation.

Is that your next project, a movie about your parents’ love story?

First, I have to finish “Algerian by Accident.” And I must figure out who I will write it with, but it is one of those movies. I think there are like five movies I need to make before I die, and that is one of them. I don’t know if it will be my next movie or after two others, but it’s on the list. Because it’s a very beautiful story about freedom that talks about a historical moment when everything was possible, like an Algerian meeting a Brazilian, you know? It is a movie about a moment when there were these possibilities.

And these possibilities don’t exist anymore?

Now there is this possibility, but at that time it was marvelous. It was almost like a Martian marrying someone from Jupiter [laughter]. It was so far away that their differences were something to celebrate. It was something that brought people together instead of striking fear.

It was a hiatus in human history, those decades [1960s and 1970s] because everything was possible, and I think: it is nice that that was possible. And even if you think about my father’s story, he breaks up with my mother and marries an Algerian woman, so you see that there was an explosion of possibilities then that I find very beautiful.

And I think there are more possibilities now to meet the different, but there is also more prejudice. And I think that what happened to them was unheard of, so it is a beautiful story to tell.

How was your trip to Algeria?

I was in Algeria earlier this year, from February till April, and since I had never been there, I decided to make a trip from Algiers to Northeast Algeria, where my father was born. This (“Algerian by Accident”) will be a documentary about that trip, which started in Marseille (France), passed through Algiers by boat, and from there to the small town where my father’s family is from, in the Algerian mountains.

We’ll start editing the movie in two weeks. This trip allowed me to understand a little bit about my father’s relation to his country. It had always seemed to me like a faraway country – because it seems close to Ceará, but it’s not – so it was a discovery of that country that is also mine in a certain way. The movie will have a format somewhat like “I Travel Because I Have to, I Come Back Because I Love You.” It’s a travel journal and a discovery journal, not only about the country but about my own father. It was very nice.

Did your father go with you?

He did, he has an apartment there [in Algiers] and when he learned I was going to make a movie, we arranged it so that he stayed there with me for three weeks. It was super nice. He broke up with my mother and got married with an Algerian woman, I have a half-sister living in France. We went the three of us, it was nice.

I don’t speak Arabic – I talk with my father in French – so I don’t even have access to the Arab culture through the language, but in this trip to Algeria with my father, it was very impressive to see how we are similar, so I started understanding how my mother met him too, because it is not that different, you know?

What did you think of the country?

It was funny being there. My name is one of the most common in Algeria, like if I was called Francisco in Brazil. It was very surprising, and my father’s family is not big, but it was very nice to know my relatives, cousins, uncles, aunts, meeting [people] who share my last name. I found myself discovering a whole new world. There is no one with my family name in Ceará, so it was an amazing adventure, and it was really nice to learn about the story of that part of the world, what its independence was like, what that emancipation meant to those countries that were subject to a very strong colonial power – in the case of England, Egypt; in the case of French, Lebanon, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria…

It was a very beautiful moment in Algeria. I was lucky to arrive in a moment of yet another emancipation, after a government that had been in office for over twenty years, and there was an occupation movement in the streets. In the whole country, actually, every Friday there are protest in the streets to return to democracy. It was really beautiful to be there on that moment.

For the last years, I have also traveled to Lebanon often. I’ve worked there as a script consultant and it has been great to discover that part of the world and see that Lebanon and Algeria are obviously very different.

I saw that you are about to release your documentary on the Syrian refugees in Germany.

I made the movie “Central Airport THF,” a documentary about the Syrian refugees here in Germany. It still hasn’t premiered in Brazil – but it’s set to premiere in August or September.

I think we should be very mindful because there is a constant effort to villainize the Arab young man, and this happened to me in France when I was young, because of my name… It was something that really bothered me and I think that, in the last few years, with the Daesh [ISIS], the invasion of Syria, people are turning things upside down and blaming the victims, because in reality those are victims of a war that was not caused only for domestic reasons but also foreign trade reasons.

For me, making this movie was important to talk about that because with each day we don’t talk about it, it only gets worse. I think that has a huge effect on future generations.

Besides this documentary, do you think your Arab background influences your work?

Yes, my Arab background does influence my work. In Brazil, they always asked me if I was Syrian or Lebanese. In Brazil, it seems that being Arab is being Syrian or Lebanese – of course this changed a lot in the last few years. In Ceará, there is a great Syrian-Lebanese presence, as well as in Amazonas and in the whole country, so this was a common question for me, and I said no, my father is Algerian.

But there was always a feeling of empathy, of “we don’t come from the same place, but we do,” you know? So, this has always been part of my identity and my background, this feeling that I was a son of an Arab. I think in Brazil we see the immigration origins as natural because we are all immigrants, except for the natives, the indigenous peoples.

And because I was first-generation. It always made it evident that I was a Brazilian from another place, you know. Even my name is weird for the Northeast and for Brazil. There are very few Karims in the country, and much less Aïnouz. I think I’m the only one, so this immigrant thing in my own country impacted the stories I tell. If you look closely, all my stories have a little of this status, not of an immigrant, but of an outsider. And I always try to put something of the Arab world into my movies. Juazeiro do Norte, Ceará, reminds me a lot of the Middle East, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria.

Brazil and the Arab world have very similar cultures, this hospitality thing, that is also very Muslim, they have much in common. When I go to Beirut, I feel like home, it is familiar to me, very close to the Northeast even.

I used to dream a lot about the Arab world, Algeria, the independent country. It was a place I imagined a lot while growing up. When I was a child, I used to receive date boxes from my grandfather, I had a dream-like relation with it.

My relation with the Arab world started as an immigrant in France, because of the relation my father had with France, and that France had with Algeria. It was very hard; it was not easy for a seventeen-year-old to arrive in France with the name Karim. It was crazy because people would ask me where I was from, and I would say I was from Brazil. And they would say, No, you are Arab, and I would say, Yes, I’m that too, but they would say I was Arab, not Brazilian. So, I suddenly became Arab when I was 18, without knowing what that meant.

That first contact was not easy at all because I was instantly cast aside – I couldn’t rent an apartment, for example. Obviously, that has changed, not much, but it changed a little since I was there, 35 or 40 years ago. “Becoming Arab” was hard for me, not because I was ashamed of it, but because I was regarded as someone from a place I didn’t know. I say now that it was funny, but I think it had quite an impact not only on my life but on my work as well.

When I moved to Fortaleza, nobody got my name – it was always Ricardinho, Paulinho, Carlinhos, never Karim [laughter]. It was crazy, impossible – until now I’m called “Ms. Karem,” and when I arrived [in France] and found out that there were other Karims beside me, there was a culture I didn’t know about, which was my father’s culture, the Arab culture, it was amazing, finding out that there are lots of us and it’s a sublime culture.

Another thing I think it’s nice to say is that my father’s family is Arab and Berber, which is indigenous people to North Africa (with a strong presence in Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia). My father comes from the mountains, and my name is Muslim – Karim means “generous” and is one the 99 names of Allah – while my last name, Aïnouz, is Berber.

Is your family religious?

My family is not exactly Muslim. We are Muslims by tradition, but we are not religious. So, I also had a relation with the modern Arab culture, when you see what the Arab culture was like in the 1960s through the 1980s, it is quite modern. I was lucky to walk into that culture through a door that was not the tradition, the religion, but a secular Arab culture, very nice, very visionary.

I felt like it was a generation thing, very different from how it is today, because now you always have this confluence of the Arab and the Muslim, but it really isn’t. We are many things, if you go to a place like Lebanon, you’ll find Catholic, Christian and Muslim Arabs. First, it was a shock to me, but then it was beautiful to embrace this culture. I feel very privileged to have these two cultures that are so different and so similar.

I’m agnostic and my mother was an atheist, so is my father. He is from a generation of the communism, the freedom, the independence. It was a very beautiful time. I see pictures of my father’s female friends in Algeria in the 1960s and they are all wearing miniskirts. There was this very free thing that I think was pushed back by religion, war issues and the invasion of Iraq, I think it has somewhat changed how we identify ourselves as Arabs.

And, just like the Brazilian culture, theirs is a very hedonist culture too. I think that doesn’t quite match the conservative path it has taken. And this is not even the majority. I think when you are in the Arab countries, pleasure is very important for them.

I also think there is something very similar between the Arab culture and the culture in Ceará. There is a Moorish thing, from the Iberian Peninsula, the Portuguese. Ceará also has the Sertão, which is a very isolated area, there is this isolation in the Northeast, and I think that’s where I found this common ground, so I could understand a little of my parents’ relationship. And there is a very striking hospitality in Ceará, a certain degree of naiveté, not in the sense of foolishness but of generosity, that I think also came from the Arabs.

Since when do you live in Berlin?

It has been ten years since I moved to Berlin. I left Brazil very early, moved to France with my father, then I left France because of that [the prejudice against Arabs]. I was very angry about the way I was being treated there. I was caught by surprise. And when I was nineteen or twenty, I moved to the United States because nobody there knew about my heritage; they knew only that I was from Brazil and had an Arab name, but nobody asked me questions about that.

I lived there for 15 years, and when I realized, it had been twenty years since I was away from Brazil, but I didn’t want to stay in the United States. I worked there for many years, and I came to live in Germany quite by chance. I won a grant to stay here for a year as an artist-in-residence. I really liked here, so I stayed, and eventually moved to an all-Arab neighborhood. Next door there is a street nicknamed Gaza Strip because every store in the street is owned by the Lebanese and Palestinians, and now there are also Syrians. So that was an appeal when I moved here because it’s a neighborhood that makes me feel somewhat close to home. It is a culture more linked to Lebanon and Palestine, of people who came here in the 1970s.

You hold a degree in architecture. How did you start making movies?

I studied architecture, then I wanted to study painting, but I was not very talented, so I moved to photography, which took me to the video, and I started working as an assistant editor, casting assistant, working as staff in independent movies. Then the cinema came with some short films; the first one I made was about my grandmother.

Then I started making feature films, not because I wanted to, but because I wanted to make a living off cinema and I realized I had to pay the bills. It was all very organic, and at that time I made my first feature film, which was Madame Satã (2002).

But it wasn’t exactly my dream – like, I wanted a career in the movies! – it just kind of happened. And I really liked the work, you know, I think it is important, it’s something that really interests me and it’s a power, the impact that fiction has on reality is very big.

I think the world is an amazing place, but it’s full of problems, so I think one needs to talk about these problems loud and clear, stir up discussions, because the impact of the cinema is huge. My plan was never to become a filmmaker; for me, it was important to be in the world and do something I liked and could make a living of, and that I would enjoy. It was something I learned from my mother, who said I could do anything, as long as I did it well.

It’s been 25 years since I started making movies. I want to keep doing it, but it’s not just that. I like other stuff. I love taking photos. It has been 30 years since I photograph. I have a collection. But it was not like I watched a movie when I was eight and said to my mother I wanted to be a filmmaker. It was not like that.

And how was the process for the movie “The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão?”

I don’t think I make movies because I need to make certain movies. I think they impose themselves on me more than I impose myself on them. “The Invisible Life” [of Eurídice Gusmão] started as a present I wanted to give my mother. She died in 2015, and that was the year I read the manuscript [of the book of the same name by Martha Batalha]. People didn’t know much about how hard life had been for a woman at that time, and the movie started from my wish to talk about that.

It was a very personal project. The book is very closely related to my mother’s and my aunt’s story. It is related to my first short film too. And the years went by, and at the development phase other issues arose. With the rise of the patriarchy we live in, a conservative moment – which is a little like a moment of desperation of the dying patriarchy, and people are getting crazy – the movie became extremely necessary.

I think some people know what they want since the beginning. I don’t. I think I was just trying things, and if I started late, I think that gave me a larger repertoire. To write a good character, for example, you must have lived with good characters. They are not born from a blank page.

In your career you alternate between fiction and documentaries.

I do fiction and documentary. For me, it’s the same, it’s cinema. It doesn’t matter if it’s fiction, experimental – what does matter is that it reaches the viewer. It’s not that different. The movie asks for the format it wants to have.

And I noticed most of your projects you write with other people.

Yes, I hate writing. I think it’s boring, I don’t like it, but I really like structuring, so I’m more like an architect of stories. I usually make the script with two screenwriters. I’m usually someone that is inside and outside the story. Which now they call showrunner.

How was it to be the first Brazilian filmmaker to win the top prize “Un Certain Regard” at the Cannes film festival?

I think it was especially important to win this prize in a moment when we see in Brazil a certain villainization of the arts, with sponsorship cuts from Petrobras, for example, concerns on culture incentive laws, such as the Rouanet law. I think it’s nice. If you Google it, I think we are everywhere with this award thing. So, the movie will be everywhere. I think the award really makes that possible.

It is wonderful that we have received this award, not just for the work, the recognition, but also as an evidence that the arts are important. And it was very beautiful, not only for Brazil but for other countries that have a cinematography that is still shaky. The first interview I gave after leaving the ceremony was to the Algerian TV. I had already talked with Canal Brasil when I was inside, but it was really nice talking to the Algerian TV. It was very thrilling. Let this be an inspiration for other filmmakers, because I think that it is also an award for our whole generation. And let this inspire the new generations that are starting now.

Translated by Guilherme Miranda