São Paulo – This is the first time three Egyptian artists come to Brazil to present their works at an exhibition in São Paulo during the Egyptian Culture Festival. In addition to their nationality and discoveries in Brazilian soil, the three of them have much more in common. On papers and canvas, politics and the Arab woman are shared themes. In an interview with ANBA, the artists talk about their work processes and resulting paintings.

Samar Kamel

Between collaged Arabic newspapers texts and paint, veiled women’s eyes stare at those who walks through the exhibition held at Club Homs. The works are by Samar Kamel, an Egyptian living in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. “I’m also a writer, so I write about women and I paint women as well. I want to put myself in it. I’m a feminist. I like to put their sufferings and their feelings, and their thoughts. And being a Middle Eastern woman, I like to put whatever they suffer with,” she says about issues that range from socials to religious problems. “That’s why I give my best tothese pictures.”

The works exhibited in São Paulo show mixed materials and possibilities. Paintings with impasto, a technique where paint is laid in very thick layers, and collage. “I love using mixed media. I like that it has different textures,” explains Kamel, who uses elements such as oil paint, acrylic paint, nail polish, and even tea bags in her paintings.

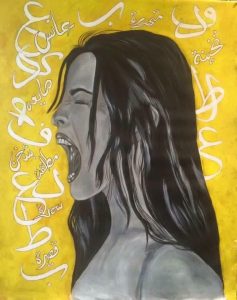

In the series exhibited in Brazil, Kamel depicts Middle Eastern traditionally or modernly clad women, who all bring expressiveness to the works. “Many of my paintings are made to provoke. For example, I have one that shows a woman screaming against a background of Arabic words. “These are things her neighbors, the society says about her, such as ‘fat,’ ‘black,’ ‘smoker,’ things like that, because I feel like in many societies, not just in Egypt, if a woman gets divorced, for example, people will talk. Women pay the price. It’s about us paying the price to live. Everything a woman do is very measured because she knows that someone will say something,” she stresses.

In her literary narratives, Kamel writes in Arabic and her works were published in the UAE and Egypt. “I’m trying to make people understand that women are different [from one another]. They aren’t just half of the society. They are the society,” she points out. Her works were in over 62 international exhibitions and fairs.

The artist curates art events, such as 2019 do World Art Dubai, where she has exhibited for four years. While visiting São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP), she took the time to come up with new ideas for her exhibitions. “I loved how they exhibit at MASP. It’s part of my job to think about these things,” said she, who saw many similarities between São Paulo and Egyptian cities.

Lotfi Abu Sariya

Lofti Abu Sariya has over 50 years of career. The Egyptian artist who lives in Belgium, draws every day. “Always people. Always women. I only draw women. Why? I paint nice things,” Lofti explains, while opening his notepad at the most recent page and starting to doodle. The creation he’s making during his stay in Brazil is a drawing of a ballerina, whose skirt is made of a collaged flower he found on the Paulista Avenue.

His different-styled works bring themes such as loneliness and the burden of the divorce for women before the society. “I think women are life. Symbols of life. And they are symbols in my paintings,” he explained. His paintings use the female figure as a starting place to also deal with other themes, such as politics. In two of his paintings, he depicted, the Arab Spring, for example.

Lofti explains that his art went through many phases. “I started with an academic style. Then I turned to the sentimental one. Then I switched to expressionism. Now it’s the start of surrealism,” he explains, showing each one of the periods in his exhibited paintings at Club Homs.

He was the head of design of Carrefour Advertising Department for European countries, including Portugal and Spain, but earlier in his career he started using his most singular format, the papyrus. The drawings are made on small pieces of the Egyptian material and glued to a larger base. The work with papyrus started in 1966, when Lofti decided to contemporarily use the paper as an art media. The first of his papyri is at the Papyrus Institute in Cairo.

Having started drawing at twelve, the artist believes he received a gift and hopes to share it. “My project is to put many paintings in museums all over the world. I believe we all speak the same language. We all speak art,” he says. “Art and culture fix what politics and violence destroy,” he wrote.

Ahmed Samir Farid

The Egyptian artist Samir Farid was born in 1969 and studied at the Faculty of Economics and Political Science in Cairo. For the past 17 years, however, Farid works in an area other than the one he’d studied for years: he’s a cartoonist. “I also draw and paint, but I chose caricatures because it’s more fun,” he says.

The artist started publishing his drawings in 2006 and, since then, he participated in national and international competition. During his stay in Brazil, Farid had a stand at Club Homs, where he offered his work to visitors. On the other hand, in his daily life he works as a freelancer and creates both caricatures and cartoons for Egyptian newspapers.

“I like several themes, but politics is also part of my education, so you can see I have many caricatures with political figures. In my cartoons, on the other hand, I try creating a dialogue. I like not using captions so that people think on what I want to convey,” he explained.

The artist believes there’s room for the number of cartoonists in the country to grow. “We have approximately 200 cartoonists, but maybe only 60 or 70 practicing [professionally],” he points out. So, Farid wants to develop another skill, learning how to teach. “I’m preparing a cartoon academy to teach arts through Facebook. I also want to do workshops for children teaching caricatures. Inviting other artists to participate,” he said, adding that the intends to increase the interest for the arts in his home country.

Translated by Guilherme Miranda