São Paulo – Instalment payments, recipes, a different way to celebrate, unheard-of words, and business, lots of business. That is some of the heritage which Arabs have brought to Brazil since the first immigrants arrived. When that was is uncertain, but the 13-vessel fleet led by Pedro Álvares Cabral had Arab crew as early as 1500. Since the first few years after its foundation, Arabs were present and influent in Brazilian society, but it wouldn’t be until the second half of the 19th century that the Syrians and Lebanese really streamed in.

Now, an in-depth look into the number of Arab natives and descendants in Brazil will become available as the Arab Brazilian Chamber of Commerce releases a groundbreaking next Wednesday (22), in an online event that will also mark its 68th anniversary.

Now, the number of Arabs and Arab descendants living in Brazil will be revealed in an unprecedented, in-depth survey set to be released by the Arab Brazilian Chamber of Commerce next Thursday (22), in an online event that will also mark the organization’s 68th year in existence.

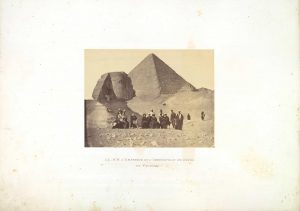

Even though scholars do not agree on a date on which Arabs first reached Brazil, they all concur that the culture and the language was already spreading among slaves prior to 1850. And then, from 1880 on, that presence became consolidated. Pictured above is the Abrão Dib family, in 1922, during their earliest times in Brazil.

According to Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) Arab Language and Culture professor João Baptista de Medeiros Vargens, Arab influence in Brazil includes Islamic people, for as far back as the first half of the 19th century, black Muslim slaves were being trafficked into Bahia. Here, in 1835, they rose up in a major rebellion which the local government cracked down on. The abadá tunics they wore and the Koran verses they kept close to their vests, however, became emblems of their religion and culture. “It’s hard to tell which countries they came from, because many of them would get shipped out of the same seaport, which was not of necessity in their own lands,” Vargens notes.

From 1840 on, wars and fighting in Lebanon and Syria drove away many residents. Their dreamland and fate was often the United States, the promising America, as well as some South America locations, like Argentina. “Brazil was not their place of choice, yet some of them would pick it, since it was also a promising destination in America. Others would come in by mistake,” University of São Paulo (USP) Arab History professor Arlene Clemesha points out.

The director of the Latin America Studies and Cultures Center at Lebanon’s Holy Spirit of Kaslik University (USEK), researcher and historian Roberto Khatlab notes that more and more Arabs flocked to Brazil as of 1880, in the wake of emperor D. Pedro <I>’s two trips to Africa and the Middle East. Although the emperor’s travels were not official in nature, his presence in Egypt, 1871 and then in Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Turkey, in 1876, ultimately introduced a new country to the inhabitants of that section of the globe.

Texts and papers on Brazil were even published in Arabic newspapers. D. Pedro II learned to read the language and took an interest in the local culture. More than that, he raised awareness of a nation with vast tracts of fertile land – which the European colonizers explored –, and one which required merchants. “D. Pedro II was a man of foresight. He’d spread the word across Europe that Brazil needed to develop its farming. But he also wanted people to engage in commerce, to make goods circulate across the territory. And he knew that Arabs were great at that,” says Khatlab.

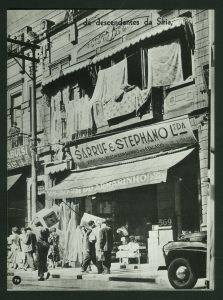

This Arab presence was crucial to the development of trade in Brazil. According to Khatlab, many of the Lebanese who settled in this promising country in the Americas brought along something they had mastered back home, from village to village: selling. They were also accomplished conversationists. In shuttling from crop to crop across the state of São Paulo and elsewhere in Brazil, they’d haul along not only their haberdashery kits of fabric, tools and items of daily use, but also news and information from one place to the next.

Arlene Clemesha remarks that for the European settlers who’d tend the fields, buying from the Arabs was a great deal: “Back then, menial labor was still attached to the customs of slavery. Settlers would run into debt at the farm shops, which their own employers owned. This wasn’t a good idea for them. They all were better off buying from the Arabs, because they could get better deals on their items,” she says.

“In working as traveling salespeople, Arab immigrants came into contact with the local population and the Portuguese language. Once they’d grow a small business, they’d send for their relatives. This economic activity meant engaging with all social strata in Brazil, and with much of the economic life, but also the Carnaval, football, the communion with folk culture,” says Vargens, pointing out that Arab-descendant families run escolas de samba in São Paulo and in Rio de Janeiro. “One of Mangueira’s greatest samba composers ever was of Arab descent,” he argues, referencing Rio’s traditional ‘samba school’ and its Hélio Turco.

Unlike Italian immigrants, who’d often sail to Brazil due to international agreements with jobs in place before they’d even arrive, Arabs would come in of their own volition. According to Khatlab, they benefited from an accord reached in 1858 by Brazil and the Ottoman-Turk Empire. As per its provisions, bearers of Turk-Ottoman passports – as was the case with Syrians and the Lebanese at that point in time – were allowed to migrate and be gainfully employed without a visa.

Since they had no bonds or ties with farmers or government, unlike the Europeans, the Arabs were able to earn their keep by working on their own, and this was key in allowing them to thrive in the new land. After being street merchants, they became businessmen and went into imports, after all they had family and contacts in Europe and across America. They introduced instalment payments, they became industrialists, restaurateurs, business administrators, hospital managers, physicians… Arabs and their descendants founded associations and clubs. They ventured into politics and economics. They went hands-on with their culinary traditions, and they enriched what Brazilians put on their plates. They brought their music, and their words contributed to Brazilian Portuguese.

The streams of immigrants

“There were many phases to Arab immigration to Brazil. From 1880 to 1910, people flocked from Syria and Lebanon to Brazil as a result of conflicts arising from the Ottoman Empire’s persecution of Christians, and of fighting caused by a lack of fertile lands. Afterwards, there were ups and downs to immigrant numbers, during World War One (1914-1918) and World War Two (1939-1945), and then immigration picked back up in the post-war. During this time, Brazilians also moved to Arab countries,” Kathlab notes.

Even after the two world wars, Arabs kept making Brazil their new home. It was thus during the Lebanese Civil War, which lasted from 1975 to 1990, then with the Palestinians in the early 2000s, and then with the fighting since 2011 in Syria. The latter case, however, involved refugees rather than immigrants – that is, people going away due to fighting in their homeland. As per numbers from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 3,326 Syrians were accepted as refugees in Brazil between 2011 and 2018, making up 40% of total asylum requests granted by Brazil during that time. Over that same period, 350 Palestinians were 4% of all refugees accepted in Brazil, with 110 Iraqis accounting for 1%.

Many of those refugees chose to live in Brazil because the country offered the conditions for them to get in without any paperwork, under a ruling put in place by former president Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). This allowed asylum-seekers to enter Brazil and then wait to get their documentation and have their applications accepted.

While Arabs left behind a flavorful gastronomic heritage, methods of negotiation and cultural footprints, Brazil also made its mark in Syrian and Lebanese land: “Some immigrants still send back money to their families in Lebanon, and this has helped develop some of the villages. There are areas where people drink chimarrão. And pastel, coxinha and pão de queijo, they’re part of the menu in the Beka’a Valley, thanks to a group of Brazilian migrants. Lebanon has also incorporated Brazilian foods and embraced Brazilian customs,” says Kathlab.

*Special ANBA report by Marcos Carrieri

Translated by Gabriel Pomerancblum