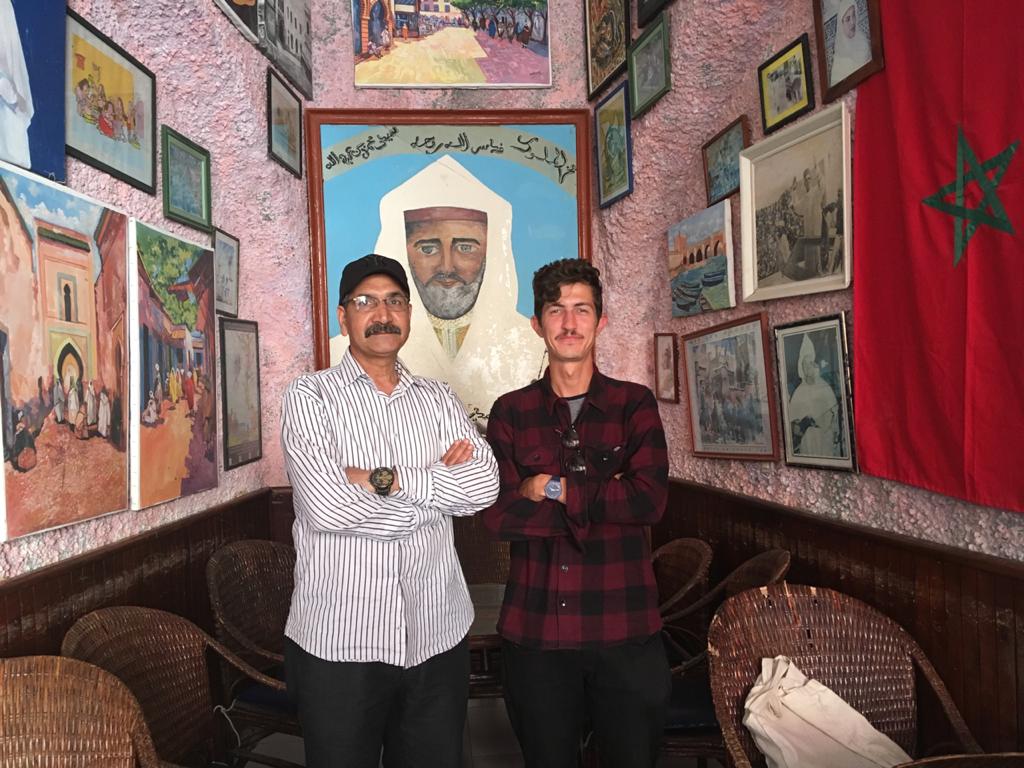

São Paulo – The multiplicity of the Arab culture is one key point of the research developed by doctor of letters Felipe Benjamin (pictured above, right). Since 2010, the young professor has focused his studies on the Moroccan dialect of Arabic, specifically of South Morocco. “The Arabic are many languages in one. The written Arabic is the standard language. When a journalist talks, for example, he uses the standard Arabic. But in everyday life, the change in the Arabic is huge. Each country has a multitude of dialects. Inside the Moroccan Arabic, you have several dialects. In older cities you hear one, in rural areas another. This is related to different waves of Arabization in each country,” the scholar explains.

Such is the case of the city of Essaouira in South Morocco, which is Benjamin’s object of study, that saw different Arabization waves, with tribes encountering different peoples over the years. But, to get there, the researcher had to start a pioneering work.

At the end of his undergraduate degree in Letters from the University of São Paulo (USP), the young man, who’s not an Arab descendant, got an unprecedent scholarship to study in Morocco. “I was there for six months studying Arabic. The call provided for five scholarships across the world. I was the only one in Latin America; the others came from the UK and the United States,” he says. His first travel ended in early 2011.

When he returned, the student pursued a master’s degree at USP, and the experience made him focus on the dialect spoke at Moroccan region of Essaouira. It was a groundbreaking study in the country, where most of the contact with the Arab culture is with Syrians and Lebanese. “In Brazil, nobody studied Moroccan literature and history. And you find nothing on dialects. It’s a new field, as nobody studies dialects of Arabic in Brazil, what is spoken in the daily life. It’s a new field of research. We’ve started something new,” he stressed. The admission of the Brazilian to the Moroccan institution even opened doors to other students, who started going to the country with a scholarship too.

In addition to the country itself, other points draw attention to Benjamin’s work. Considered an example of tolerance because of the coexistence of different religions, the studies on the dialect of Essaouira are few and far between. “When I started this study about the urban and rural Arabic, I began bringing data for an atlas made by German authors about Arabic dialects, which didn’t mention the city yet. It was a way for Brazil to cooperate with this field, which is dominated by the Europeans,” the researcher said.

The port region had a great influence from the Portuguese, who occupied the village before the city was even founded in 1765. But it’s the presence of Arab Jews that makes the history and language of Essaouira more peculiar. “Morocco has a significant population of Berber and Arab Jews. They are Jews that speak Arabic, but it’s a very specific Arabic that many people call Jewish Arabic. This city once had half of its population Muslim, half Jewish, as well as diplomats and merchants from several countries across the world. There was even a trade office from Brazil in the city,” he explained.

The pioneering aspect of the topic earned him a scholarship for a doctoral exchange program at the University of Cádiz in Spain. “I had the chance to study with one of the greatest researchers of Moroccan Arabic, Jordi Aguadé Bofill. The Spanish and the French are give the most attention to Morrocco,” explained Benjamin, who returned to the Arab country to do interviews and some field work in what was a very anthropologically enriching experience.

The researcher’s sources included some of the last Jews that have lived in Essaouira, as well as Muslim Arabs, people from the rural area of the country and even one tribe that lives around the city. “It’s a process – it takes time for people to understand and open up to what I’m doing. For an Arabic speaker, it sounds weird when I ask, ‘How do you say this or that,’” he said. He listened to and recorded dozens of people.

For Benjamin, the openness came when the Moroccan realized the dedication of a foreigner to study their language. “They open up when they see that you are interested in their dialect. The way that Moroccans talk is very stigmatized. When you watch an Arab channel and a Moroccan person talks, they even put subtitles on. This occurs because in Morocco you have several lexical borrowings from the French, the Spanish, the Berber. You have a huge linguistic contact, that’s the diversity in the local speech,” he says.

After getting his doctor’s degree last February, Benjamin has continued his studies at the University of Cádiz in Spain, analyzing now the lexical borrowings of the Portuguese to the Moroccan dialect. “It’s a development of the research I did before, something new. Everyone studies the Hispanisms in Arabic, but nobody studied the Portuguese words. They are actually few from what I’ve seen, but since the Portuguese spent some centuries in Morocco, some words came into the Moroccan Arabic dialect,” he explained. Although they seem to be few, words like “garfo” [fork] used in the city of Casablanca, for example, are evidence of the Portuguese influence in that dialect.

Now, Benjamin teaches at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), while continuing his researches. But the professor stresses the importance that the specialization program in Arabic of USP still holds as it’s the only one in the country. “Brazil has one graduate program to train researchers in Arabic studies and letters, which is something that stands out in Latin America as a whole. The students here have been going to Arab countries, participating in exchange programs, humanitarian work. So, Brazilians have gotten into Arabic studies and put themselves out there,” he stresses.

Because of his studies, the Brazilian has been invited to lecture in universities like the University of Granada, University of Cádiz, University of Coimbra in Portugal, Instituto Cervantes of Tétouan in Morocco, and the University of Zaragoza. The latter will publish Benjamin’s thesis, and some of his articles will also be published in a book in Germany.

In the middle of a career passing through several foreign institutions, Benjamin believes in the importance of the contributions of the study of languages in Brazil. “It’s the case of the work that students and professors have developed in nonprofits that help refugees in the country. “People say that the investment in science must have a return, but in Brazil they don’t realize how the research in linguistics is relevant for society, which goes far beyond Arabic translations into Portuguese. When we had the refugee crisis, Brazilian students went to the lines to help people in formalities in hospitals, together with doctors, lawyers and social workiers. People from both UFRJ and USP give Portuguese teach in nonprofits. Many Arabic speakers that came didn’t even speak English. So, the students also acted as communitarian interpreters, a key activity for refugees to have their basic rights. This was made possible thanks to the public investment in Arabic studies” he stressed. He has worked as a volunteer interpreter at Cáritas de São Paulo, helping refugee people.

Translated by Guilherme Miranda