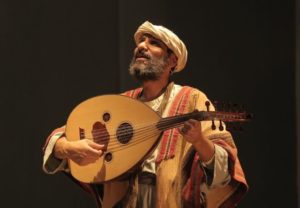

São Paulo – Sami Bordokan started playing the lute when he was six. Now that he’s about to turn 50, they are still inseparable friends. It’s his primary passion and tough he plays several instruments, it’s the lute that Sami Bordokan is usually seen with in photos and on the stage. It was as natural for him to learn how to play it as it was to learn Arabic. At home, where music was the resting state of his family, Arabic was the only language they spoke. “My father was a very skilled lute player and an exquisite singer, but he never worked as a professional artist,” he said. “My grandfather, a priest at the Greek Melkite Church, where they speak the Byzantine language, possessed a magnificent voice. All my uncles and aunts were awarded with beautiful voices and an exceptional musical talent, and I grew up hearing them sing, but I’m the first in the family to become a professional musician.”

Embora os pais tenham nascido em vilarejos a vinte minutos de carro um do outro, em Akkar, no Líbano, eles só viriam se conhecer no Brasil, para onde migraram em busca de melhores condições de vida. Além da iniciação precoce no alaúde, um dos mais antigos instrumentos que se tem notícia, Sami estudou violão clássico e popular, órgão clássico e piano. Adolescente, partiu para uma aventura na terra dos pais onde acabou morando por nove anos. Frequentou a Universidade Saint-Esprit de Kaslik (Usek), na qual foi aluno no departamento de música oriental. “Tive aulas particulares com mestres renomados e me aprofundei na teoria musical oriental (Maqamat Charquie) e no canto clássico árabe, mais especificamente o Muashah Andaluzo”, explica.

The Arab music dates back from the ancestral culture of the Middle East and at a given moment, it becomes a major pillar of erudition of society of that time. “As the Arab Islamic civilization progressed from the seventh century on, we saw an intense process of erudition in music,” Bordokan says. “Note that at that time music was part of medicine. Al-Kindi, who’s considered the father of the Islamic philosophy, Avicenna and Al-Farabi, who were great names of the music in that period, were all doctors and skilled lute players.”

If on the one hand music was part of the classical background, on the other hand it was passed down for generations thanks to what Bordokan calls an “extraordinary capacity of the Arab peoples to maintaining and perpetuating popular traditions.” It’s hard to talk about one Arab music only, as each region has its own cultural singularities, thus building up a rich, diverse musical mosaic. “Concurrently, a giant erudite repertoire is shared by all Arab peoples, like Muashah Andaluzo for example.”

Bordokan goes from classical to folkloric and also includes Brazilian genres in his repertoire. In his website, you can see a video of him and other musicians playing a choro but with the lute instead of the cavaquinho or mandolin. “Brazilian music is part of my imagery, as I’m Brazilian, after all, and I really love this country and its extremely rich musical tradition. I really enjoy building musical bridges between these two cultures.”

When he came back from Lebanon and performed for the first time in a classical concert hall, he was surprised and delighted with the receptiveness of Brazilian ears to ancestral Eastern music. Almost thirty years later, he is preparing an album that is a synthesis of his career, with a mix of classical Arab repertoire and original songs that trace a path between the East and Brazil.

Actor by accident

The musician has also written for plays, films and television, such as the telenovela Órfãos da terra and the miniseries Dois irmãos, based on the novel of Brazilian writer of Lebanese descent Milton Hatoum, launched in 2017. It was then that Bordokan became an actor by accident when he was invited by director Luiz Fernando de Carvalho to play a role. “I’d never imagined I would act until I got the invitation,” confesses Bordokan, who took a liking to the art and is now preparing to come back to the stages as the lead of The Prophet.

Read more: Musical The Prophet premieres in São Paulo

Based on one of the world’s most popular books, by Lebanese poet Gibran Khalil Gibran, the play directed by Luiz Antônio Rocha is expected to premiere again in March or April 2023, when the book turns 100. “It’s an enormous responsibility, and I have devoted myself completely to be up to this challenge,” says Sami Bordokan, who besides singing, playing and acting is also responsible for the musical direction of the play together with his brother Willian Bordokan.

Report by Débora Rubin, especially for ANBA.

Translated by Guilherme Miranda