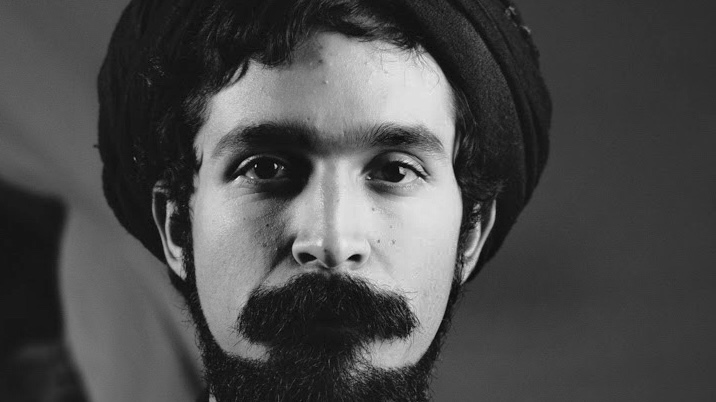

São Paulo – Tattooing artworks inspired by aesthetics and the history of Islamic and Arab art and Middle East folk culture has been Marcus Abraham Mubarack’s (pictured above) occupation since 2013. The artist of Arab descent who lives in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sull decided to print on his skin the themes he has been curious about since he was little. “I studied History and Anthropology in college. I didn’t graduate, but I’ve always been extremely attached to it,” recalled the tattoo artist.

Mubarack remembers the puzzle he has been putting together to reconstruct his family’s steps before they came to Brazil. On my father’s side, they came from the border between Turkey, Syria, and Iraq in the early 1910s. “I was putting together a few pieces of what each one told. What I know is my father’s family came from this Ottoman region at the end of World War I. And my grandmother’s family were refugees of the Assyrian genocide; they were Christians. Here, my grandmother met my grandfather, who was from Egypt,” he recalls.

In Gramado, Rio Grande do Sul, where he was born, they were one of the few Arab families. “All over town, my father was [known as] the Turk. That part of the [Middle East] presents an amalgamation of things forming a unity of identity. Several groups overlap each other. But where we lived, I didn’t have much contact with that. When I came to Porto Alegre, I met more people that came from the same context. Here, I was able to dig deeper because there is a mosque, an Arab restaurant,” reveals the artist.

History and Tattoo

Mubarack enrolled in the History major at a college in Novo Hamburgo and started researching artistic movements in the Middle East. During this period, he started working as a tattoo artist. “I’ve been drawing since I was a kid, but it was never my intention [to work with it]. I started tatting to pay for my studies,” revealed Mubarack.

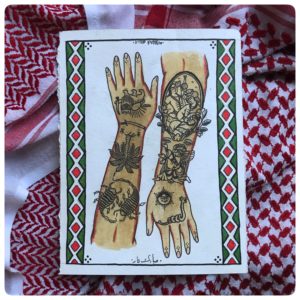

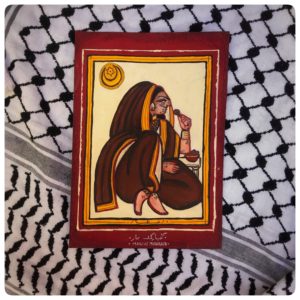

The path towards arts had references within his family, with people working with embroidery, wood crafts, theater, and even gardening. Mubarack has also incorporated techniques and inspirations from mosaics, Arabic calligraphy, Arab arts, and Persian miniatures. “One thing I like about folk art is that it’s a collective expression rather than an individual one. These are ‘standard’ things everyone knows about, but they don’t have a single author. It is seen as collective art,” he pointed out.

Currently living and working in Porto Alegre, the artist usually visits other cities, such as São Paulo and Curitiba, where he works in partners’ studios. “But I also work with painting and illustration. Like what I did for Des-oriente-se,” he explains, mentioning the artwork he developed for the brand of the Brazilian page about the Middle East.

The profile of those seeking Mubarack’s tattoos is varied. From professors and scholars of Human Sciences to people captivated by the aesthetics of his works. The illustrations are made available to even more people.

In São Paulo, the artist partners with Galeria Estranho, an art gallery that reproduces and sells his illustrations in high-quality fine art print formats. “The cool thing is they do this work of dissemination and sale even abroad. There is a lot of demand abroad. I see there are a lot of buyers from Iran. There are also many artistic collectives in Lebanon, and Palestinians and people from the diaspora who follow my work too,” he explains.

Contemporary inspirations

The tattoo artist’s influences are even more far-reaching. Among contemporary Arab artists inspiring the Brazilian are the Palestinians Burhan Karkoutly and Sliman Mansour; Iraqis Afifa Aleiby, Hayv Kahraman, Wassma Al-Agha, Mahoud Ahmed, Faisal Laibi Sahi, Esther Elia; in addition to Syrian Louay Kayali, and Yemeni Hakim Al-Akel.

In his works, there are illustrations inspired by materials from political campaigns to children’s books. “The region there, as in Iraq, is very multicultural. It was the world’s knowledge center, and I think it’s really cool artists bring that up a lot. It’s cool to bring this to tattoos, which are seen as something more popular. It’s a way of appropriating a culture that is mine too,” he concluded.

Translated by Elúsio Brasileiro