São Paulo – “We could say that I’m 75% Lebanese,” says Juliana Ganan, a native of Itajubá in Minas Gerais, Brazil with Lebanese DNA from her entire maternal family plus her paternal grandfather. An agricultural engineer with a master’s in International Relations, she had a stint working for the Interamerican Development Bank (IDB) in the United States. Back in Itajubá, Ganan opened her first business – the coffee roasting microbusiness A Tocaya Torradores de Café.

The Ganans are no newcomers to coffee. Juliana’s grandfather moved from Lebanon to Brazil when he was 20. After years of working as a traveling salesman, he managed to help his father buy a coffee farm. “My father would grow coffee as a commodity. We’d go down to the farm every weekend. But that’s a different product than what I do nowadays.”

The land is no longer in the family, but her taste for coffee stayed with her and grew more refined. “Odd as that may seem, I found out about specialty coffee when I was away from Brazil, and then I came back to work with it here. Coffee is a great passion of mine, and I didn’t love my work, so I kept taking courses and then I decided to work with coffee,” says Ganan, who underwent barista training in the USA and took a course in roasting in Berlin. “I went to school to learn about light roasts. I started my courses in 2013 and I returned to Brazil in 2016. These days we have lots of good roasts here in Brazil, but back then there wasn’t much.”

The older people in the family are tradespeople, but the younger Ganans are ‘all over the place,’ as she puts it. “Roasting was my first business. One of my older brothers has always been a tradesman and he’s great at sales. He gave me a few pointers, but it was a shock to me. I was used to having things go smoothly in the corporate world. Things took longer and got more expensive than I had planned. But every entrepreneur I ever speak with will tell me that’s the way it is.”

Juliana oversees two women when it comes to doing the roasting work. They work to emphasize each feature of the beans – which are sourced locally in the Mantiqueira de Minas, with additional product coming in from Caparaó and Montanhas Capixabas. A Tocaya sells its product to cafés and restaurants as well as online to end buyers.

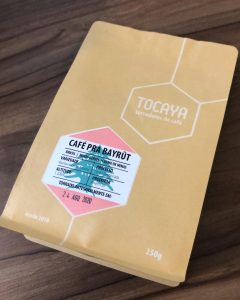

Café para Bayrut

Last year saw Ganan take her first trip to Lebanon. A writer for coffee blog Sprudge, she stopped by to see the Kalei Coffee Co., where she met owner Dalia Jaffal. They kept in touch, and the Port of Beirut blast prompted Juliana to write about crowdfunding efforts to help Beirut’s tourism-driven businesses, including the cafés.

But she wanted to do more for the people of Lebanon. “I decided to do something via A Tocaya as well. I got some coffee from a grower who’s our partner and we created the Café para Bayrut (Coffee for Beirut) campaign. We funneled some of the proceeds to Live Love Beirut, a relatively unknown organization that our contacts in Lebanon recommended to us.”

The campaign was met with support from A Tocaya consumers. “It ended way before we were hoping it would. There was one group in Brasília that purchased 40 packs, and in the end we donated twice the amount we were expecting, because the real-to-dollar rate was terrible at that point,” Juliana said.

Glad that the campaign worked out well, the roast master looks back on her trip to the Levant country, where she saw Byblos, the Bekaa Valley and Beirut. “I met with a cousin of mine and it was really cool, and really cultural. The funny thing was everyone looked like my family. Even the way they’d speak. I plan on going again and staying longer.”

Back in Brazil, the pandemic also changed Juliana’s routine. She saw some of her main partners the restaurants and cafés – closed for months on end. One solution was to put in time and strategy into selling direct to end buyers online. “We had been doing before, but that was a negligible share of our sales. Since the pandemic, revenue from online sales has gone from 5% to 36%. We’re having a sale which I plan to keep going until next year, we’re giving free shipping on orders over BRL 150 in some areas. It encourages people to stock up on goof coffee,” she said.

Ganan learned a lesson from the pandemic, which has taken a toll on the Brazilian specialty coffee industry. “We are trying to restructure our processes and to adapt to this new business model, which is more about going online than anything else. But if the pandemic has taught me anything, it was to not make any plans. One step at a time.”

Translated by Gabriel Pomerancblum